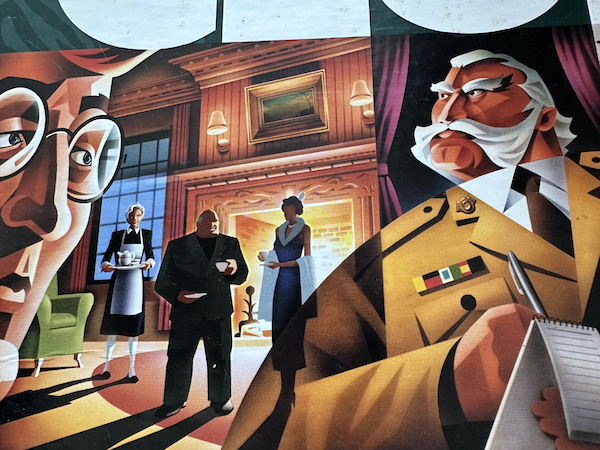

Image: “Clue” by Parker Brothers. Photo is from the author’s personal set, reproduced here under Fair Use guidelines and without intent to infringe.

Experts have been predicting the death of the network perimeter for 25 years—as long as I’ve been doing this “cyber” thing. From Dan Geer in the mid-90s to the Jericho Group in the 2000s to the more recent Zero Trust movement, no chestnut is hoarier than the idea that the network is dissolving, and that its dissolution is inevitable because of economics, enlightened self interest, and market forces. Move apps to the cloud! Focus on your core by renting software-as-a-service instead of running it on-premises! Give employees freedom to work remotely! Et cetera.

As a CISO, I have my own opinions about this. Yes, the perimeter is dissolving, and has been for a long time. We hold this truth to be self-evident. But it is also wrong. The endgame will come far sooner than most people think. Enterprises won’t dissolve their perimeters voluntarily because the market’s invisible hand pull them along—slowly or quickly, depending on their risk appetites and technology transformation plans. They’ll do it because they have no choice. Putting it another way, the perimeter won’t pass away peacefully as part of a planned and orderly transition—it will die suddenly and violently and be given a Viking funeral.

Here’s why. Attackers are going after edge devices like never before, because they are vulnerable—and I’d argue, fatally so. Vendors that sell devices that sit on the perimeter’s edge—VPNs, load balancers, remote access appliances, web security devices, and email servers—are caught in an endless cycle of one zero-day vulnerability after another. Vendors are also disfavoring further investments in their on-premises gear, steering both R&D and their customers towards cloud services. IT teams, distracted by the Big Shiny that is the cloud—and stretched thin by a competitive labor market—can’t protect edge devices, and can’t fix them fast enough. Because of this, CIOs now face an impossible choice: very quickly move their edge services to the cloud, or be inevitably attacked and compromised.

Consider Citrix. In June 2023, threat actors began circulating a zero-day vulnerability targeting the Citrix NetScaler appliance, an edge device that is commonly used to load balance application traffic, provide remote virtual desktop access (VDI), and deliver mobile email via ActiveSync. By exploiting a flaw in the device, attackers were able to gain shell access on the box, which became a staging ground for additional attacks access inside the victim’s network. On July 18th, Citrix released a patch. Large-scale attacks against thousands of organizations ensued just a few hours later. Few organizations have volunteered that they were compromised, but we know that at least 70,000 NetScalers still live on the Internet right now. But the hits kept coming for Citrix. In October, the vendor released a patch for another critical vulnerability known as CVE-2023-4966 aka “Citrix Bleed”, which organizations have struggled to fix and is now being exploited en masse.

Citrix isn’t the only edge device maker with issues. In September 2023, Cisco had its turn via a zero-day vulnerability targeting the ASA Virtual Private Network (VPN) appliances, which was implicated in the Akira ransomware attacks. Another pair of vulnerabilites in October targeted Cisco IOS XE devices. In this latter case, reportedly over 40,000 devices were compromised by attackers implanting backdoors into victims’ networks.

How about Microsoft? The company has been spectacularly successful at moving its email customers to Exchange Online. But over 150,000 organizations still run its aging Exchange on-premise solution, including over 30,000 in the United States alone. These servers require constant care, feeding, and protection. In February 2020, four zero-day exploits enabled a Chinese threat actor group, known as Hafnium, to take over 60,000 on-premises Exchange servers worldwide. In September 2022, another pair of zero-days gave attackers additional ways to compromise email mailboxes. These vulnerabilities were sufficiently concerning that my then-firm’s cyber-insurance carriers—and quite a few clients—asked us whether we had taken quick action (we had).

In short, it is clear that the bad guys are going after the perimeter like never before. No vendor that sells edge devices escapes with a clean record. Not the three I mentioned (Citrix, Cisco, or Microsoft). Not F5, not Palo Alto, and not Fortinet. They have all had their share of vulnerabilities. IT teams have had to scramble to patch or shield all of them.

A skeptic might scoff: well, attacks on the perimeter are not new. True. But do you think the answer is simply to patch faster? How fast is fast enough? Insurers and clients expect that IT teams have expedited processes for patching and emergency fixes. Disciplined IT teams in large organizations with strong change management practices can push emergency patches in twenty-four (24) hours or less. I’ve been privileged to work in firms that could do it in less time than that. But what if the attacks start coming within two hours, as they did with the recent Citrix zero-day? What if your firm is unlucky enough to be targeted by a state actor using an exploit for which no patch exists? Worse, what if the exploit targets edge devices that are end-of life and cannot be patched?

I’d argue that the speed and frequency of attacks on edge devices have reached a tipping point. Very few IT teams will ever be fast enough to get ahead of vulnerabilities targeting their edge devices—I’d peg the number at less than 25 organizations globally that stand a fighting chance. Your company is not one of them. It is plainly a matter of physics: attackers can marshal and exploit weaknesses far faster than the defenders can fix them. Their OODA loops (observe-orient-decide-act) turn faster than those of the defenders.

What this all means is that the on-premises edge is done. Stick a fork in it. Your commodity edge networking and application devices and servers—Exchange, ADFS single sign-on (SSO), VPN, remote desktop, load balancing—will invariably be compromised unless you can get rid of them. It won’t matter whether you’ve got a superstar CISO or a heroic IT ops team. That is why the perimeter won’t fade away slowly, but will die all at once. CIOs are now on a forced march to move their edge infrastructure to the cloud, because if they don’t, they’re gonna get popped.

What does this mean? The cloud offers alternatives, none of them perfect but all of them better than the status quo. Instead of running virtual desktops on Citrix appliances you can’t find talent to manage or patch, move them to Azure Desktop. If you are using 20-year-old Active Directory Federation Services for internet authentication—and you really should not be—move SSO to Okta, Ping, or SecureAuth. Rather than continue to expose frequently attacked VPN endpoints to the internet, roll out Zscaler, NetSkope, or Palo Alto’s Global Protect to remove ingress points from your network, shield applications, and provide safe outbound web access. And crucially: remove your biggest and fattest target by moving Exchange to Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace.

None of these solutions are panaceas by themselves, and they introduce additional vendor risks. But by adopting cloud-based edge infrastructure, CIOs and CISOs get four big wins:

First, other than the public website presence and any custom hosted apps, the network edge disappears completely. There is simply no exposed commodity infrastructure attackers can exploit. In addition to the clear risk reduction benefits conferred by an edge that isn’t there, IT and security teams escape the patch-and-pray cycle that is sapping morale and diverting attention from more strategic issues, such as safeguarding user identities, locking down privileged access, and splitting your network into smaller segments.

Second, by moving edge services to cloud vendors that specialize in offering them at scale, CIOs transfer a large chunk of their risks away from their teams. That is what cloud providers’ “shared responsibility models” are all about. Customers are responsible for approving access to the vendor’s services and for granting privileges. CISOs can’t be naive about the risks that come with cloud services and will need to build expertise with these new platforms. That’s because within the shared responsibility model, enterprises still have enough rope to hang themselves: they can grant elevated privileges to too many low-skilled people, or use application features inappropriately. Capital One found this out the hard way with AWS. But CIOs no longer have to worry about patching device firmware or fiddling with low-level appliance configurations. Cloud vendors are responsible for keeping their infrastructure free of security defects, operating their platforms in a controlled way, and providing the features customers need. When vendors mess up—as Microsoft did this past summer, spectacularly, and as Okta has more recently—it isn’t the CIO’s or CISO’s problem. IT teams are out of the edge infrastructure maintenance business forever, and can spend far more time securing their data. That’s huge.

Third, by removing your on-premises edge devices, CFOs save money on their cyber-insurance premiums. In 2022, cyber-insurance costs rose by 62%, fueled by the ransomware epidemic and coming on the heels of a 90% increase the year before. At least one analysis of cyber claims data has shown that enterprises with on-premises Exchange servers were three times more likely to file a claim than those using a cloud-based email provider such as Google Workspace. Carriers know their claims data and are not stupid. Within 18 months, you can expect that any use of edge devices on your network perimeter—regardless of how well you say you patch them on your insurance questionnaires—will escalate your cyber coverage costs. As a bonus, as cloud vendors increasingly automate reporting of adherence to recommended practices, the cost of applying for and maintaining cyber insurance insurance will decrease. Carriers will have finer-grained visibility into your actual posture on an ongoing basis, allowing them to tailor premiums far more precisely.

Last: by dissolving what’s left of the perimeter, employees will be happier and CIOs and CISOs will make their teams more valuable. Instead of having to continue to maintain specialty expertise in technologies that aren’t valued in today’s market, their teams get to focus on much cooler tech (AI! Software defined networking! Zero trust! Passwordless authentication!), which in turn makes them more marketable. Ask your staff whether they’d rather renew their Cisco CCNA credentials for yet another year, or get a new CCKS cloud security certification. The question answers itself.

These four wins—removing the perimeter from your attack surface, transferring responsibility for infrastructure maintenance to cloud vendors, and upskilling your team—are compelling all on their own.

But whether you find these reasons compelling or not, it really doesn’t matter, because you don’t have a choice. Threat actors are forcing you to get rid of your edge devices. You must shut them down before you get shut down.

The perimeter is dying at last. The game is up. Threat actors did it, with the zero-day, on the edge device.